|

Summer 1999 (7.2) Farhad Khalilov

_____

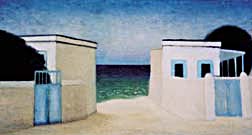

Right: "In the Field", 70 x 230 cm, oil on canvas, 1996-97. Community of Artists In 1962 and 1963, while I was in art school, I lived in Buzovna (an outlying district in Baku) with Kamal and Javad. We stayed in a dilapidated house near the old bathhouse. In the evening, we would return to the city. Though Javad was not so well known at that time, I cherished his opinions about my work. Rasim Babayev, Togrul Narimanbeyov and Gorkhmaz Afandiyev also worked there. Sattar Bahlulzade joined us later-an artist I came to love very much for his ability and his love of art. Our group had a real sense of unity. The one thing that we had in common was that we spoke our minds. I wouldn't really call myself a dissident. But an artist is an artist and nothing can prevent him from saying what he thinks. He will always find a way to express what is in his heart, no matter what the cost. All of us had that kind of fighting spirit. Kamal and I used to take our palettes and go out into nature together. We would stay there hours and hours and work. Kamal was a great artist. Sometimes people ask me how I've been able to keep my own style after being in such close contact with these other great artists. Even Kamal would show his works to me and ponder: "It resembles Javad's works, doesn't it?" He was afraid of copying someone else's art. I would try to convince him that his works were not at all like Javad's. Official Barriers After I finished art school in Baku, I entered the Stroganoff Technical Art College in Moscow. But after a year, I wanted to come back home. I missed my girlfriend, my colleagues and Buzovna. At school, I overheard a conversation between the Department Head and one of my teachers. The Department Head was insisting that the teacher arrange it so that I wouldn't pass. (It turns out that my classmates and teachers had gone behind my back and reported to him everything that I had ever said or done there.) Right after that, I went to the Department Head and told him about my decision to return to Baku. He approved and said that there was no use staying at the school any longer anyway. So I returned to Baku. I started participating in exhibitions in 1967; two years later, I became a member of Azerbaijan's Artists' Union. At the time, my individual exhibitions would open in Moscow, not Baku. There were several unofficial places in Moscow where one could organize exhibitions, such as the editorial office of the magazine "Yunost" (Youth). Left-wing artists were given the opportunity to exhibit their works at this editorial office, in its small halls. I got married in 1968, then entered the extramural department of the Moscow Fine Arts Institute. Many famous Russian artists were graduates of this institute, including Favorsky and Goncharov. Once Goncharov told me: "You were born an artist. Why are you studying here? I know why-because you need that diploma in your country." For one of our exams there, we were required to sketch a nude figure. The teachers argued about my work but eventually gave me an excellent mark. It was my first ever. In 1973, I painted a work three meters wide entitled "Call". Everyone was astonished by this work. I had depicted a sunset, showing how-as the day draws to a close-the sun sets and the horizon is red. My work was not accepted. Vasilyev, the KGB leader at the time, asked me, "What are you 'calling' for?" In order to support me, Tahir Salahov observed, "Don't you see that the horizon is red? This is an allusion to Communism." In fact, I was not a member of the Communist Party. I didn't want to mention the fact that during the 1970s, my father was second in charge only to Heydar Aliyev. My father was one of the so-called "pure Communists". When he was six years old, he had come to Azerbaijan with his grandmother from Ardabil [Southern Azerbaijan, Iran]. At age 27, he worked as a factory manager, even though he had no relatives or influential friends to help him attain the position. In 1942, during WWII, he asked the government to send him to the front. But they didn't want to lose him because he was managing two munitions factories. He received a Lenin prize that same year. Despite my father's attitude towards the Soviet system, I opposed it. Once he asked me: "Why don't you join the Communist Party?" I told him that I had no time. The truth is that if I had I joined the Party, I would have spent all my time arguing with other Party members. There were so many artificial persons among them. I had no time to get involved in exposing their dishonesty and lies-I was involved in art. That was the first and last time that my father asked my opinion about the Communist Party. After that, the subject was closed. He retired before I was elected President of the Artists' Union. Artists' Union The Artists' Union was established around 1942 or 1943. In the 1960s and 70s, it had 300 or 400 members; today it has 800 members, plus 100 young artists in the youth department, meaning artists in their thirties who have just graduated from art school. It used to be that an artist had to take part in an all-Union (USSR) exhibition in order to become a member of the Artists' Union. To participate in an exhibition, a board had to accept one's work. If the board didn't approve, they would send the works back. After each exhibition, a committee of experts from the Ministry of Culture would select which works to buy. The money intended for the Artists' Union was transferred to the Ministry of Culture so the Union had a close relationship with the Ministry. When the Soviet Union collapsed, we reestablished an independent Artists' Union in Azerbaijan with its own charter. (Before, there was one general charter for all of the Artists' Unions in the USSR.) Today, the Artists' Union doesn't depend on any Ministry; it is a completely independent organization. The main duty of the Artists' Union is to encourage artists to create quality work. We try to do this by helping artists with material aid. For instance, in the past ten years, I've seen to it that more than 120 studios were allocated to artists. Many of them are found in the lofts of apartment buildings where there is more space and access to good natural lighting. After I was elected President, my greatest concern has been whether I would be able to fulfill my official responsibilities and still have time to work on my own art. These days, I still create my own works, even though my time is very limited. I still manage to find time to go to my studio and work, often in the evenings. I'm happy that Azerbaijan is an independent country today, and that's why we do our best to bear every difficulty. Artists are living under difficult conditions. Not every person can be an artist-you have to prove yourself to the world. I tell my friends not to complain about their hard conditions, since they have chosen this way for themselves. If you can't live without art, you will carry on despite hunger, cold and other difficulties. We have a very talented group of young artists in Azerbaijan. They suffer tremendously from a financial point of view, but this is a wonderful chance for them to improve their ideological outlook. Now they can finally speak their own mind and paint without any constraints. During the Soviet period, when artists had financial problems, they would usually take an order, work on it and get paid. Today, artists don't have this kind of opportunity. In its place they have freedom. There's nothing in the world like freedom for an artist. Farhad Khalilov

is President

of the Artists' Union. He can be reached at the Artists' Union,

19 Khagani Street. Tel: (99-412) 93-62-30. |